loading...

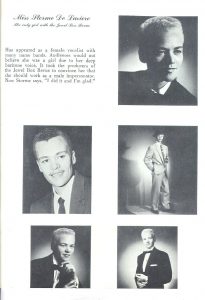

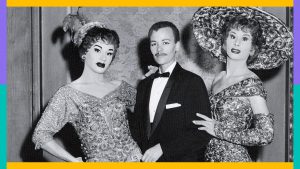

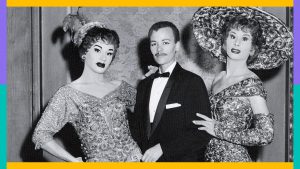

Imagine it’s the 1960s and you see a line of glamorously dressed women glide onto the stage. Following behind them is a dapper young man, dressed in a well-fitted suit, with a thousand yard stare and a James Dean demeanor. You are at the Jewel Box Revue, and the program tells you that the women you see on stage are actually female impersonators, drag queens, save for one member of the cast. By the end of the performance, it is revealed that the one woman onstage is the stoic, suave emcee, played by a woman named Stormé DeLarverie.

Female impersonation, gender-bending, and what we would now call drag were not actually uncommon in the 1950s and 1960s. A show that was particularly popular was the Jewel Box Revue, which featured multiple female impersonators and one male impersonator, Stormé. Stormé DeLarverie was a young lesbian presenting as a straight man (which was common for butch lesbians in the 1950s and 60s) in Chicago when she was recruited for the Jewel Box Revue, where she was able to make a name for herself. The Jewel Box Revue was widely celebrated, and Stormé was the emcee and music director for the Revue for 14 years. She lived with relative notoriety and always with the love of her partner, Diana, a dancer. Stormé was born in New Orleans as a mixed race person in the 1920s, on an unknown date. Her mother was the servant of her father, and due to anti-miscegenation laws, she was born without a birth certificate. She faced a lot of violence in her youth, and was aware that she could not present the way she wanted to in New Orleans, which might be why she moved to Chicago and became a singer after high school. In Chicago, she dressed and presented as a straight man. No one knew her there, so it was easier to live as she pleased. She had some success as a singer; she traveled on the road and eventually became a member of the Jewel Box Revue. She ran in circles with the likes of Nina Simone and other great singers of the time. For Stormé, the Jewel Box Revue also functioned as a kind of chosen family. She said that not only did she respect the other performers greatly, but she saw them as friends worthy of her protection.

The Jewel Box Revue wasn’t just seen as an incredible drag show, it was seen as an incredible show—a top notch performance with only the best performers on stage. This play on gender was something that could only happen theatrically, since the laws of the time still criminalized “cross-dressing”. But Stormé set trends off the stage as well, stating trends for other lesbians of the time. This approach to fashion can be found today in the “gender-bending” styles of cis men and queer women: Janelle Monáe, Harry Styles, and Kristen Stewart, to name a few.

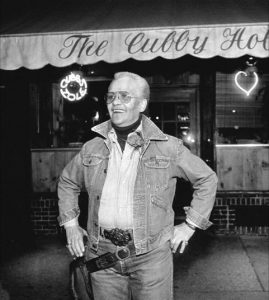

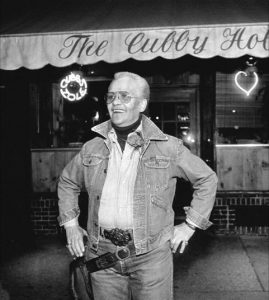

Stormé wasn’t just an LGBTQ+ pioneer of fashion and a defier of gendered clothing expectations. She also played a key role in the1969 Stonewall Riots and was committed to protecting the LGBTQ+ community. While the history of what specifically happened at the Stonewall Riots can be unclear, Stormé was there that night, and is rumored to have thrown the first punch at a cop. Police raids like the one that happened June 28th 1969 (the night of the Stonewall Riots) were common in bars primarily trafficked by LGBTQ+ Black and Indigenous people of color, but on that night the patrons of the Stonewall Inn had had enough. Stormé was sick of her friends being harassed, and she was tired of the “ugly” (Stormé used this word to describe bias and hatred) that she experienced every day. Despite the fact that Stormé was allowed to be who she wanted to be on stage, her presentation still put her in danger on the street. Maybe this was why two months after Stonewall, Stormé left the Jewel Box Revue and switched career paths. Around the same time, tragedy hit Stormé’s life. Her partner of 25 years, Diana, died. Stormé reportedly always kept a picture of Diana in her wallet until her own death. After this loss, Stormé became a bodyguard. Friends say that Stormé definitely knew how to throw a punch from her difficult childhood in New Orleans. She worked for rich NYC families during the day, but at night, Stormé was a bodyguard for some of the most well-trafficked gay and lesbian bars in the city. She was known to protect young queer women at all costs, especially from the gaze of predatory straight men. She wore a gun on her hip, and was sometimes called the Butch Cowboy of NYC. She was a member of the Stonewall Veterans Association, but she didn’t talk much about what happened that night. Rather she took more action, protecting young gay women on the streets of New York. She began working at the Cubby Hole, a lesbian bar. There she met and became friends with Lisa Cannistraci, who tended bar and would eventually go on to own the Cubby Hole.

Even after Stormé retired from working at the Cubby Hole, Lisa continued to pay her. When Stormé stopped showing up to collect her payments due to physical health problems and dementia, Lisa and another longtime friend of Stormé’s became her legal guardians, and set her up in the nicest assisted living facility they could find, one that offered Stormé freedom and appreciated what she had done for the LGBTQ+ community. Stormé lived out her days there until she passed away in May of 2014 at the approximate age of 93. In the end, the members of the community she had given so much to gave back to her, the Butch Cowboy of NYC. I first encountered this story when listening to an episode of The Nod, a podcast with the tagline: “Brittany Luse and Eric Eddings gleefully explore all the beautiful, complicated dimensions of Black life.” You can find the podcast episode here.

The primary thought that came up for me when hearing about Stormé was that there must be so many people we never hear about in LGBTQ+ History. Storné spent her life prepared to lay down everything for the LGBTQ+ community she loved. How many more LGBTQ+ people owe ourselves to? It is also nothing short of beautiful that Stormé was taken care of in her old age, and that people decided to care for her because they knew she was important. How do you support your LGBTQ+ community? How do you support your LGBTQ+ elders?

Sources:

https://www.npr.org/2020/06/26/884080764/they-dont-say-our-names-enough

https://queermusicheritage.com/fem-jewl.html#:~:text=The%20famed%20Jewel%20Box%20Revue,be%20from%20the%20early%2060s.

https://www.gq.com/story/storme-delarverie-suiting

[{"id":52023,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: Monday, Dec 18, 2023"},{"id":52022,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: Thursday, Nov 9, 2023"},{"id":52021,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: Thursday, Sept 14, 2023"},{"id":51973,"title":"Career Connect: Learn How to Recruit & Mentor LGBTQ+ Students"},{"id":51972,"title":"Career Connect: Learn How to Recruit & Mentor LGBTQ+ Students"},{"id":51971,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Friday, Dec 15, 2023"},{"id":51970,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Monday, Nov 20, 2023"},{"id":51969,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Friday, Nov 3, 2023"},{"id":51968,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Tuesday, Oct 24, 2023"},{"id":51967,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Wednesday, Oct 11, 2023"},{"id":51962,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Tuesday, Oct 10, 2023"},{"id":51961,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Friday, Sept 8, 2023"},{"id":51960,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Monday, Aug 28, 2023"},{"id":51535,"title":"Stop The Hate National Train the Trainer"},{"id":51100,"title":"Advisor Academy 2023"},{"id":51091,"title":"Camp Pride 2023"},{"id":51004,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: Tuesday, June 20, 2023"},{"id":51003,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: Monday, May 22, 2023"},{"id":51002,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: Monday, April 17, 2023"},{"id":51001,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: Monday, March 20, 2023"},{"id":51000,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: Monday, February 27, 2023"},{"id":50999,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Friday, June 30, 2023"},{"id":50998,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Thursday, June 15, 2023"},{"id":50997,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Friday, May 26, 2023"},{"id":50996,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Friday, May 12, 2023"},{"id":50995,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Friday, April 21, 2023"},{"id":50994,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Friday, April 7, 2023"},{"id":50993,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Friday, March 24, 2023"},{"id":50992,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Thursday, March 9, 2023"},{"id":50991,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: Friday, February 24, 2023"},{"id":50710,"title":"Stop The Hate Train the Trainer - West Coast Regional Training"},{"id":50479,"title":"September 16: Campus Pride Founder's Day"},{"id":50474,"title":"WORST LIST: Talk Back Roundtable featuring Campus Pride & REAP"},{"id":49923,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: December 16, 2022"},{"id":49921,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: November 21, 2022"},{"id":49919,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: October 14, 2022"},{"id":49918,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: September 23, 2022"},{"id":49916,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: December 12, 2022"},{"id":49915,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: December 9, 2022"},{"id":49914,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: January 30, 2023"},{"id":49913,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: January 27, 2023"},{"id":49911,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: November 11, 2022"},{"id":49910,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: October 10, 2022"},{"id":49909,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: October 24, 2022"},{"id":49908,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: September 9, 2022"},{"id":49907,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: August 15, 2022"},{"id":49906,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: August 5, 2022"},{"id":49903,"title":"Stonewall Riots - Then & Now :: LIVE IG"},{"id":49851,"title":"Juneteenth :: LIVE IG"},{"id":49574,"title":"International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia"},{"id":49573,"title":"Agender Pride Day"},{"id":49572,"title":"Harvey Milk Day"},{"id":49543,"title":"IG LIVE Celebrating Campus Pride Month"},{"id":49469,"title":"International Asexual Awareness Day"},{"id":49467,"title":"Happy Campus Pride Month"},{"id":49410,"title":"International Transgender Day of Visibility"},{"id":49296,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: July 15, 2022"},{"id":49295,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: July 14, 2022"},{"id":49293,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: May 6, 2022"},{"id":49290,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: March 11, 2022"},{"id":49289,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: April 18, 2022"},{"id":48920,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: June 20, 2022"},{"id":48919,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: May 9, 2022"},{"id":48918,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: March 25, 2022"},{"id":48917,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: January 31, 2022"},{"id":48916,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: June 24, 2022"},{"id":48914,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: June 10, 2022"},{"id":48913,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: May 27, 2022"},{"id":48912,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: April 15, 2022"},{"id":48911,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: March 28, 2022"},{"id":48910,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: February 11, 2022"},{"id":48909,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: January 28, 2022"},{"id":48830,"title":"Happy New Year from Campus Pride"},{"id":48793,"title":"Human Rights Day"},{"id":48777,"title":"Happy Pansexual Pride"},{"id":48756,"title":"Happy Holidays from #LubeLife"},{"id":48722,"title":"International Day of Disabled People\u2019s"},{"id":48676,"title":"Campus Pride Spotlight Feature: Washington State University"},{"id":48671,"title":"Campus Pride Spotlight Series Presents: University of Wisconsin (UW Milwaukee)"},{"id":48640,"title":"IG LIVE SPEAKER SERIES: NATIVE AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH"},{"id":48564,"title":"Intersex Day of Remembrance"},{"id":48140,"title":"National Coming Out Day Celebration"},{"id":48137,"title":"#PronounsDay: Celebrating International Pronouns Day"},{"id":48134,"title":"UNF Diversity, Equity, Inclusion Career Summit in partnership with Campus Pride"},{"id":47842,"title":"Founders Day :: Sept 16"},{"id":47732,"title":"Bi Visibility Day :: Sept 23"},{"id":47537,"title":"20th Anniversary Spotlight :: University of Pennsylvania"},{"id":47536,"title":"20th Anniversary Spotlight :: University of Michigan"},{"id":47535,"title":"20th Anniversary Spotlight :: University of Colorado Boulder"},{"id":47524,"title":"20th Anniversary Spotlight :: Purdue University"},{"id":47523,"title":"20th Anniversary Spotlight :: Portland State University"},{"id":47516,"title":"20th Anniversary Spotlight :: Princeton University"},{"id":46939,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: December 3, 2021"},{"id":46938,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: November 1, 2021"},{"id":46937,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: September 24, 2021"},{"id":46935,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: August 23, 2021"},{"id":46932,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: December 8, 2021"},{"id":46931,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: November 19, 2021"},{"id":46930,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: October 11, 2021"},{"id":46929,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: September 17, 2021"},{"id":46928,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: August 20, 2021"},{"id":46927,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: July 30, 2021"},{"id":46840,"title":"Campus Pride Give OUT Day Virtual Pride Celebration"},{"id":46598,"title":"Understanding Pride within Native Indigenous Two Spirit Communities,\u00a0Special IG Live for Pride Month\u00a0"},{"id":46499,"title":"Stonewall Riots: Pride & Activism,\u00a0Special IG Live\u00a0for Pride Month"},{"id":46330,"title":"Juneteenth and Black Queer & Trans Futures: A Reflection"},{"id":46253,"title":"20th Anniversary :: Alumni Feature IG LIVE with Lauren Neidigh"},{"id":45841,"title":"Mental Health Month,\u00a0Special IG Live\u00a0w\/ EqualityMD"},{"id":45802,"title":"20th Anniversary :: Alumni Feature IG LIVE with Rebby Kern"},{"id":45710,"title":"20th Anniversary :: Alumni Feature IG LIVE with Mark Travis Rivera"},{"id":45585,"title":"2021 Digital Camp Pride"},{"id":45579,"title":"National Youth HIV + AIDS Awareness Day,\u00a0 Special IG Live\u00a0w\/ Mario Campos"},{"id":45493,"title":"20th Anniversary Spotlight :: Kenyon College"},{"id":45488,"title":"20th Anniversary Spotlight :: University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire"},{"id":45480,"title":"#LAVGRAD National Lavender Graduation Ceremony"},{"id":45478,"title":"Campus Pride Month"},{"id":45358,"title":"Side Bi Side: Unpacking Biphobia & Creating a Culture of Inclusion"},{"id":45139,"title":"20th Anniversary :: Alumni Feature IG LIVE with Katie Barnes"},{"id":44992,"title":"March Volunteer Madness"},{"id":44990,"title":"Women's History Month"},{"id":44796,"title":"20th Anniversary Spotlight :: University of Texas at Dallas"},{"id":44791,"title":"20th Anniversary :: Alumni Feature IG LIVE with Romeo Jackson"},{"id":44611,"title":"20th Anniversary Spotlight :: Montclair State University"},{"id":44567,"title":"Black History Month"},{"id":43719,"title":"Send a Love Note to LGBTQ Youth"},{"id":42244,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: June 16, 2021"},{"id":42243,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: May 12"},{"id":42241,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: April 23, 2021"},{"id":42242,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: March 19, 2021"},{"id":42240,"title":"Stop The Hate Online Training :: Feb 26, 2021"},{"id":42220,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: June 11, 2021"},{"id":42219,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: May 19, 2021"},{"id":42218,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: February 19, 2021"},{"id":42217,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: April 12, 2021"},{"id":42215,"title":"Safe Space Online Training :: March 12, 2021"},{"id":38244,"title":"Camp Pride 2020"},{"id":38010,"title":"WigOUT :: Buy Tickets"},{"id":37638,"title":"Campus Pride National LGBTQ-Friendly College Fair 2019-20"},{"id":36844,"title":"Advisor Academy 2019"},{"id":36842,"title":"Camp Pride 2019"},{"id":36325,"title":"Safe Space - SouthEast Regional Training","payment":"default"},{"id":36311,"title":"Stop The Hate Train the Trainer - SouthEast Regional Training","payment":"default"},{"id":35917,"title":"Campus Pride National LGBTQ-Friendly College Fair 2018-19","payment":"default"},{"id":35047,"title":"Stop The Hate Train the Trainer - UW Platteville","payment":"cc"},{"id":34014,"title":"Advisor Academy 2018","payment":"default"},{"id":34009,"title":"Camp Pride 2018","payment":"default"},{"id":32591,"title":"Campus Pride National Job & Career Fair Program 2017-18"},{"id":32504,"title":"Campus Pride National LGBTQ-Friendly College Fair Program 2017-18"},{"id":29863,"title":"Stop The Hate Train The Trainer - Napa"},{"id":28908,"title":"Advisor Academy"},{"id":28306,"title":"Camp Pride"},{"id":31049,"title":"Campus Pride National Job & Career Fair Program 2016-17"},{"id":27556,"title":"Campus Pride National Job & Career Fair Program 2016-17"},{"id":26692,"title":"Campus Pride National LGBTQ-Friendly College Fair Program 2016-17"},{"id":31048,"title":"Campus Pride Homecoming & Awards Banquet"},{"id":26197,"title":"Campus Pride Homecoming & Awards Banquet"},{"id":25310,"title":"Stop The Hate Train the Trainer - Wisconsin"},{"id":24624,"title":"Advisor Bootcamp"},{"id":24559,"title":"Camp Pride"}]